By Stephanie Teasley

Back in June, CBS News reported that due to “thousands of well-paid techs” living in California’s Bay Area, a family residing there with an annual earning of $117,000 was now considered low-income. The article was accompanied by a picture of a rundown house, complete with a leaky roof that sold for $1.23 million. CBS’ report came from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which estimated the median price for a single-family home as $947,500.

This story was published across a few different mediums and the comments that people left were mixed with outrage, perplexion and disbelief. There was one comment though that perfectly summed up the situation: “This is the natural outcome of unchecked gentrification meeting archaic housing policies.”

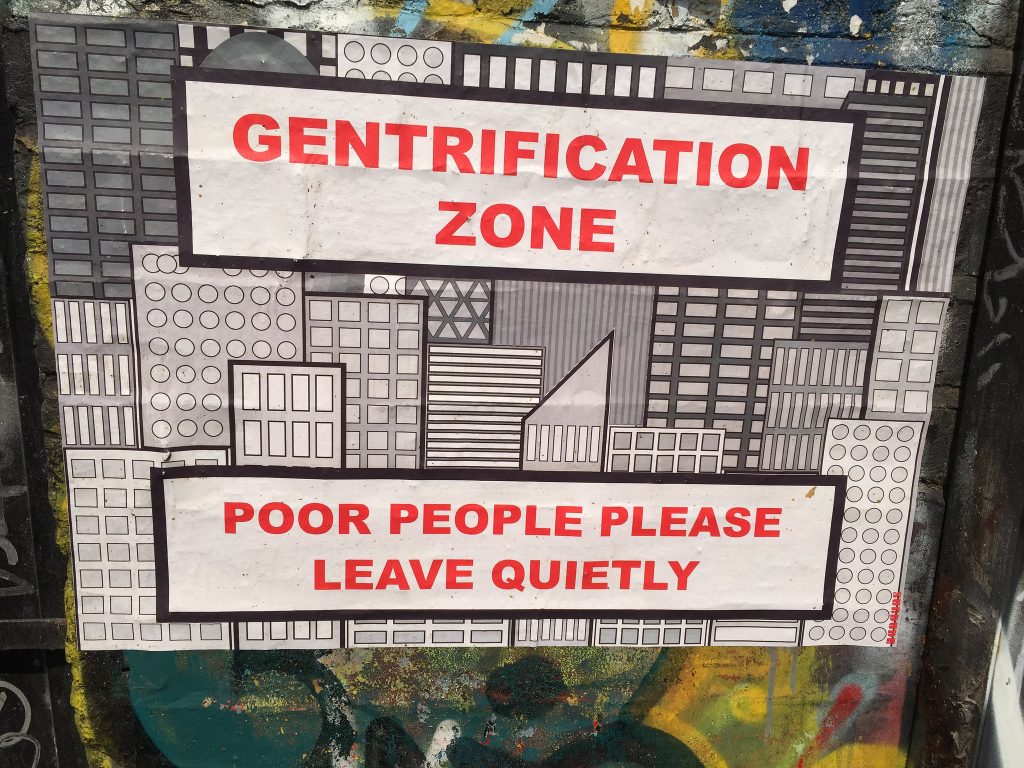

Gentrification is defined as the process of renovating and improving a house or district so that it conforms to middle-class taste. Another defines it as the process of renewal and rebuilding accompanying the influx of middle-class or affluent people into deteriorating areas that often displaces poorer residents. Urban Dictionary’s definition is a bit blunter:

When “urban renewal” of lower class neighborhoods with condos attracts yuppie tenants, driving up rent and driving out longtime, lower-income residents. It often begins with influxes of local artists looking for a cheap place to live, giving the neighborhood a bohemian flair. This hip reputation attracts yuppies who want to live in such an atmosphere, driving out the lower income artists and lower income residents, often ethnic/racial minorities, changing the social character of the neighborhood.

Urban Dictionary

It also involves the “yuppification” of local businesses; shops catering to yuppie tastes like sushi restaurants, Starbucks, etc… come to replace local businesses displaced by higher rents.

Gentrification was first used in 1964 by sociologist, Ruth Glass, who coined the phrase after seeing the poor, blue-collar residents of a poverty-stricken London neighborhood displaced and pushed out of their homes for the upper-class.

There have been a handful of articles arguing that gentrification is a good thing because there are newer and nicer developments that benefit the neighborhoods and communities. Other articles have argued that it’s all a myth and that there is hardly anything bad about it (spoiler: it’s not a myth.) While Glass was the first to give it a name, the act of gentrification or displacement, is deeply rooted in America. There was the bombing of Black Wall Street, a heinous act of domestic terrorism deeply rooted in racism, that Oklahoma did not acknowledge in its state’s history until 1996. Going back further in history, there was the theft of land and resources as well as the displacement of native Hawaiians and Mexicans from the southwest. Even further back, the Trail of Tears and the displacement of Native Americans from their own land. History has shown that it is never the minorities who benefit from displacement; our country does everything in its power to prevent this.

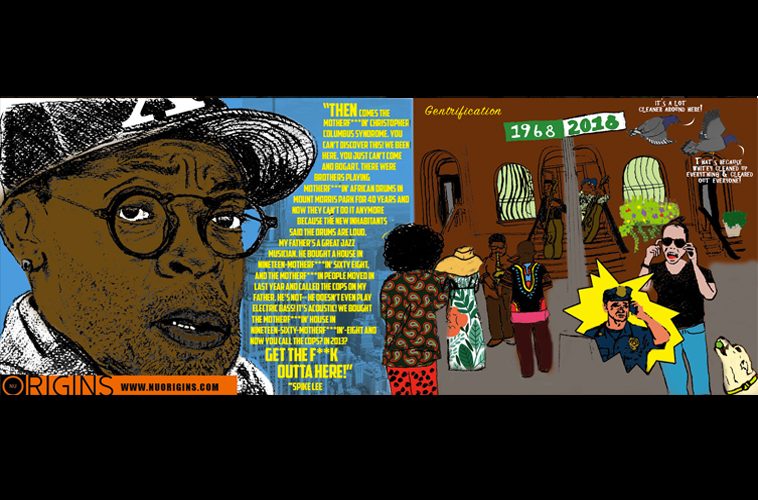

It is why some, like Spike Lee, took umbrage with the argument that gentrification is beneficial for all. Back in 2014, Lee was doing a lecture in honor of African American History Month at the Pratt Institute when the question of gentrification came up. Lee’s answer was in response to this New York Times article that, like others, gave a favorable view to gentrification. Lee asks why it took an “influx of new white people” to make things better for predominantly black neighborhoods, mentioning how the gentrification of Harlem and the Bronx was dismantling the community:

Spike Lee

“Then comes the motherf***in’ Christopher Columbus Syndrome. You can’t discover this! We been here. You just can’t come and Bogart. There were brothers playing motherf***in’ African drums in Mount Morris Park for 40 years and now they can’t do it anymore because the new inhabitants said the drums are loud. My father’s a great jazz musician. He bought a house in nineteen-motherf***kin’-sixty-eight, and the motherf***in’ people moved in last year and called the cops on my father. He’s not — he doesn’t even play electric bass! It’s acoustic! We bought the motherf***kin’ house in nineteen-sixty-motherf***in’-eight and now you call the cops? In 2013? Get the f**k outta here!”

Lee’s rant is great, especially his comparison of gentrification as more of a colonizing event rather than some life-enhancing, do-gooder moment. In a targeted move in 1976, New York City shut down 34 fire stations in poor, largely black and Latino neighborhoods. Over the next decade, seven Bronx census tracts lost virtually all of their buildings, and another 44 tracts had lost more than half. This was due to spending cuts; many factories decided to follow the white population to the suburbs, leaving the urban poor in neighborhoods with very little job prospects in increasingly run-down neighborhoods. The people left behind did what they had to survive and get by with what they had. These residents of Harlem and the Bronx that would have liked to live in nicer houses filled with working appliances would have loved to see their neighborhoods cared for and cleaned up and their local businesses thriving and hiring. That desire has always been there but like Lee says, those desires and wishes did not seem to matter until white and richer residents started moving in.

Last year, The Atlantic’s Gillian B. White reported on journalist Peter Moskowitz’s book, ‘How to Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood.’ According to White, the book provides “much-needed clarity…about a slippery concept.” Moskowitz says that while improvements in areas and cities by people who have finally recognized the uniqueness and diversity of these places is good, over time, gentrification starts to diminish those very attributes that attracted people in the first place. For instance, Lee’s father and other musicians having cops called on them for something they had been doing for decades.

Moskowitz gives post-Katrina New Orleans as an example of this. The city was devastated by the infamous hurricane and was exasperated by the lack of government response. The hurricane displaced 250,000 people, over half the population and thousands of people flocked to New Orleans as volunteers to help rebuild the area. Many stayed, drawn in by the city’s history as well as its famous food and music. The transplants did help rebuild the city by opening up various small businesses but Moskowitz points out that there was a disproportionate amount of rebuilding help when comparing the richer neighborhoods to the poorer ones. Articles were published urging middle-class families to move there or else the poor would move back and disrupt the progress. Apparently many heard the call because a study released last year found that in order to rent a two-bedroom house in the New Orleans-Metairie area, a person would need to make $18.54 an hour, or almost $39,000 annually. The average pay rate for the area is around $16 an hour and Louisiana’s minimum wage is just a little over $7 an hour.

So how did it get there?

Gentrification.

In 2012, the state of Louisiana designated the area a “cultural district”, meaning that new businesses could operate tax-free. That was great except the old businesses there were told this didn’t apply to them and were left to fend for themselves as new restaurants and shops opened up around. As more and more white people moved into the area, they became concerned with the long-time residents still in the neighborhood. In 2013, a meeting was held where the new residents decided to hire a private security -which was paid for by hiking local property taxes – to patrol the area. It didn’t pass because the proposal defenders (all white, according to Moskowitz) relented when the black residents raised their concerns that the extra security would exasperate the police harassment they were already experiencing.

In Los Angeles, many articles have been written about the gentrification of Inglewood and how black people are not only losing their places but their spaces too. Season two of Issa Rae’s HBO series, Insecure, subtly touched on this – spoilers ahead – when Issa called Lawrence to get the rest of his belongings from the apartment they once shared because she was moving out. The show alluded that she was moving because the rent was rising due to gentrification. Want more proof? When Issa’s coworker referred to Inglewood as “I-wood” and Issa’s incredulous reaction to it.

Last November, Journalist Erin Aubry Kaplan wrote an opinion piece in the L.A. Times about the gentrification of Inglewood, Kaplan’s home for the last 13 years. She reflects on how Inglewood, once a predominantly white neighborhood became a prominent and significant black city in America.“Our neighborhoods are our strength, our visibility. Leimert Park — a flashpoint of gentrification now — put Afrocentric culture on the map, literally, and has long been a hub of black civic and political organization.”

Once again, it’s not that the long-time residents don’t want to have nice things; it’s that the nice things come with people who often disrupt the community and what it has built.

As Kaplan said, “It’s an enduring American truth: Whatever black people have can be taken away.”

Is there anything that can be done about gentrification?

It is a tough situation because the reason it thrives is due to support from the government: city, state, and federal.

Stay factually informed and get involved with your local community to familiarize yourself with local officials. Voting is important, especially at the lower levels, so vote and research everything and everyone to see what connections they have to any corporations or companies. Others have suggested getting involved in grassroots movements, that help build up local and community groups.

Stay involved, stay informed and stay fighting.