In grade school, when Career Day came around, the children that were most excited to bring their parents to school, were the offspring of lawyers, firefighters, and policemen. The lawyers had reason to hold their heads high due to the widely perceived monetary success that they are viewed to enjoy, while the firefighters and policemen had their prestige and reputations as “community heroes” to fall back on. The sacrifices made, and risks firefighters cannot be disputed.

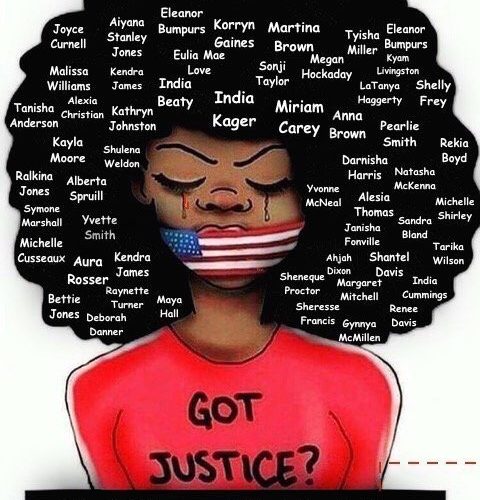

Policemen, however, may have earned a false reputation for nabbing the “bad guys”; a perception of modern-day cowboys, if you will. With such a heroic mystique surrounding them, it is no wonder that the cowboy’s shadow conceals the extreme measures taken against Black females.

This past Thursday, the New York Public Library held a Teach-In Forum to discuss Police Violence at the Schomburg Center in Harlem. The discussion featured authors Andrea Ritchie and Paul Butler, moderated by Dr. Khalil Gibran Muhammad. The interactive discussion revolved around the shameful reality that police violence not only victimizes Black men but Black women as well who suffer from this oppression in numerous ways.

Ritchie subscribes to the idea that police violence is not projected through the lens of Black women. This is a reasonable assessment when you consider the countless videos of oppressed Black men that have circulated. Furthermore, Ritchie feels that if the adequately documented incidents involving Black women included in various statistics measuring excessive force, the disparity that exists between Blacks and whites would be even higher.

“Black women suffer from mass incarceration, too,” said Ritchie.

So, could one surmise that omitting the negative police experiences of Black women is purposely fulfilled, whether to maintain the prestige of the modern-day cowboy or to downplay the issue? Alternatively, perhaps, there’s more of a ripple effect when depicting Black men in compromising positions.

Paul Butler feels the castration and emasculation of Black men that have taken place over the course of time has resonating effects. When you have Black men so falsely perceived as “threatening,” what stronger message can be sent to their women and children to reinforce the oppressive power structure than to punish their protector past the point of submission? What’s more, how is it possible that the Black man may not even invoke the highest level of uneasiness?

Ritchie alleges that Black women can be seen as more threatening than Black men. How can that be, when the Black man has historically embodied the ultimate opposition to racist white men? Further evidence of this is the historical sexual assault of the Black man’s better half, to assert power over the Black man. Contrary to popular belief, Ritchie stresses that sexual assault against Black women is alive and well in these modern times, with the vehicle being the policing system that’s currently in place. All of this being said, Ritchie makes a profound point that it’s mighty ironic how the police, among the most dominant and powerful men in the country, manages to remain in the shadows during the national conversation being had about sexual assault. Is this the way the system is supposed to work?

Butler subscribes to any solution that doesn’t target individuals but focuses on the system itself. Butler claims that the system is working the way it’s supposed to work and that the system must change to cause significant change. The criminalization strategies, such as the initiative against marijuana, must be abolished. If these tools aren’t done away with, the police will still be perceived as modern-day cowboys when Career Day comes around again.

“Abolition of the system equals de-incarceration,” said Muhammad