Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Ghana, and South Africa are just a few of the African nations that have sought to deepen their ties to the People’s Republic of China through one or more key initiatives, namely infrastructure and education. While appearing to run parallel – increased commercial ties notwithstanding – there is one issue that has thrown a dark shroud over these transcontinental relationships – racism and discrimination.

In April of this year, as videos of acts of racism and discrimination towards Africans and African-Americans in Guangzhou, China went viral, mainstream, and streaming across a wide array of social media and media platforms, what may have once been the subject of low murmurs, mere spattering of articles, or an occasional expose’ came glaringly to the forefront to reveal a deep-seeded undercurrent of prejudicial treatment of minorities in the People’s Republic.

Again, for those who still doubt that Black people and particularly #AfricansinChina are being targeted we feel it is our duty to share this. A sign at a @McDonalds restaurant seems to make this perfectly clear pic.twitter.com/FaveKrdQHi

— Black Livity China (@BlackLivityCN) April 11, 2020

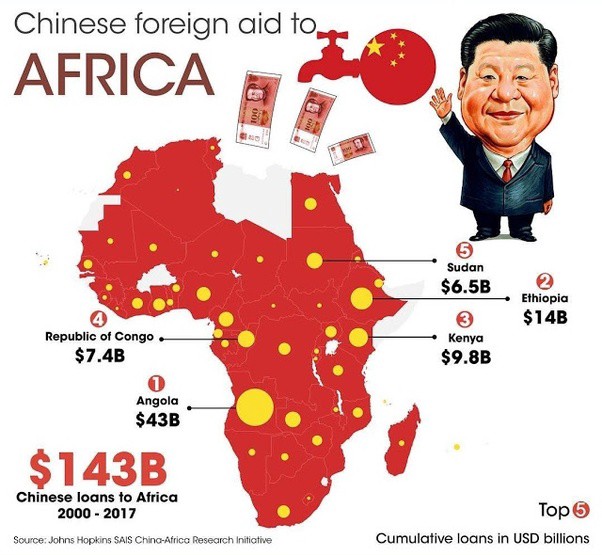

Soft power is the proverbial description given to China’s full-court step towards closer commercial, economic, and social ties with an African continent that only a few decades ago strode beyond the pale of colonialism. At least the coin of this phrase, particularly in regards to China’s foreign policy towards Africa, can be traced as far back to 2007 and the 11th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party then-led by President Hu Jintao. Since then, billions have been poured into a gaggle of multilateral trade deals and economic initiatives to cultivate and strengthen the “soft power” footprint now-President Xi Jinping so strenuously wants to broaden. By 2015, Beijing was prepared to make good on its endeavors when President Xi announced a $60 billion earmark for funding and loan support, over three years, for African students to study in the People’s Republic.

Record numbers of prospective African students, from a myriad of countries consequently part of the “Belt and Road” infrastructure packages, flocked to apply to study in China. Though, according to a number of interviews conducted by The Conversation in a January 2020 article, many students, “were suspicious of the Chinese motives for the training,” and “many believed the awards were meant to favor Chinese interests,” African students studying in China grew from 1,793 in 2003 to 81,562 in 2018 – according to figures provided by the Chinese government.

For Tanzanian students, who numbered 1400 in 2014, that number more than doubled to 3,320 in just two years’ time. For Uganda, scholarships for their nation’s students to study at Chinese universities added 39 more in 2019. And at the most recent Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) the People’s Republic pledged 30,000 scholarships for Africans. As of this year, China eclipsed both the U.S. and the U.K in Africans studying abroad in their respective universities, no doubt to accomplish what Chinese Ministry of Education described as an effort “to tell China’s story well and spread China’s voice.”

Besides the more advanced facilities and more readily available technology which African students often admit, surpasses those of their local universities, Chinese scholarships are exceedingly generous, therefore adding to their attractiveness. Considered more feasible and affordable, China’s scholarships for bachelor, masters, and doctoral degrees are front-loaded with extravagant extras that include money for materials, free accommodations, living allowances, medical care, and medical insurance. Because all Chinese universities are funded by and answer to the Communist state, namely the Ministry of Education, Beijing can offer packages private and state universities in the US., for instance, can provide.

But as scores of African students have reported, there is a dark underbelly to China’s generosity. Though seldom publicized, it seems the racism and discrimination directed towards African students, by their accounts, appears to be more prolific and systemic than others care to mention.

“Perceptible hierarchies are observable in Chinese attitudes towards the different ethnic and nationality groups congregating in China,” was how the phenomenon was described in an April 2018 International News Lens article, just as the Chinese government boasted, that same year, a prospective increase of international students to 500,000 by 2020.

The Deputy Ambassador of the People’s Republic of China in Uganda, Chen Huixin in 2019, boasted his nation’s transcontinental educational initiatives were an “offer for scholarship opportunities in line with a commitment to building the capacity of Ugandan students and strengthening the China-Uganda diplomatic relationship,” this same year the South China Morning Post reported that many students from Africa who study in China “feel the sting of prejudice” and often “feel unwelcome.”

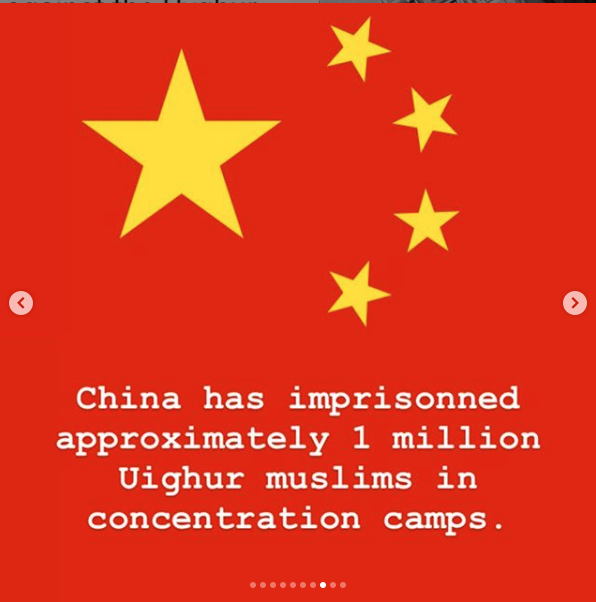

Also, by late 2019, reports of the ill treatment and forced internment of the Ulghers, a Muslim minority in China, in concentration and forced labor camps were coming to the fore. At least 1 million Ulghurs, by UN and U.S. estimates, were being involuntarily placed in what came to be known as “re-education” camps. According to an August 2019 article in The Atlantic,” over the course of an indoctrination process lasting several months, they were forced to renounce Islam, criticize non-Islamic beliefs and this of fellow inmates, and recite Communist Party propaganda songs for hours each day.” Those not interned are also subjected to wantonly discriminatory practices such as arbitrary arrests for harmless and contrived offenses such as growing a long beard, calling family members abroad, and having too many children.

There are also reports of detainees being forced to eat pork, drink alcohol, as well as being told Islam was a form of mental illness, labeling their religion as a “type of poisonous medicine, which confuses the mind of the people.” Further allegations by former detainees included incidents of torture and murder of inmates, prompting the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China to label the Chinese government’s actions as “the largest mass incarceration of a minority population in the world today.”

There are also reports of detainees being forced to eat pork, drink alcohol, as well as being told Islam was a form of mental illness, labeling their religion as a “type of poisonous medicine, which confuses the mind of the people.” Further allegations by former detainees included incidents of torture and murder of inmates, prompting the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China to label the Chinese government’s actions as “the largest mass incarceration of a minority population in the world today.”

For African students studying in China, subjected to what appeared a racist response to the COVID-19 pandemic, may have only been one of many tragic highlights to a long-standing and largely ignored problem. Indeed, “what makes the issues different in China,” according to an April 2020 article for The Diplomat, “is how easy it is to encounter racist behavior and beliefs…blatantly and matter-of-factly expressed,” by both individuals and institutions alike.

An African goes to a store in China and shows the security guard his green health code, which means he has tested negative for the #coronavirus.

Watch what happens next.

Guangzhou, China, May 19th, 2020. #AfricansInChina #RacismInChina #ChinaIsRacist #Chinazi #CCPvirus pic.twitter.com/DSC9Mbqzza

— Things China Doesn't Want You To Know (@TruthAbtChina) May 20, 2020

Students at Zhejiang Normal University (ZINU), one of the most popular higher education destinations for foreign students, many of whom from Africa noted, “racism was embedded in educational institutions and, in both daily interactions and university school programs,” which “often created the experience of second-class citizenry.”

Located in a metropolis Jinhua, which prides itself on its show of culture, African students roundly proclaimed that they felt there was preferential treatment towards their European counterparts and at every level there was little in the form of accountability. At universities throughout the People’s Republic, African students got the sense their Chinese classmates perceived African students required lower entrance scores to attend university and that scholarship funds, which local students felt would have gone to them, were being spent on African students instead.

Similar sentiments have been expressed about Chinese workers and businessmen who operate in African countries, particularly as part of the “Belt and Road” initiative. One example of this has manifested over the last few years in Kenya, which welcomed approximately 40,000 Chinese workers and business owners into their country. Despite the Chinese government’s claims that such projects represent broadening and strengthening ties between Chinese and African peoples, as in the case of Chinese workers in Kenya, “many [Chinese] employees live together in large housing developments and are bussed back and forth from work,: limiting any social or cultural engagement by Chinese workers with Kenyan citizens. Even Kenyans that work for Chinese businesses in their country reported there are times they are referred to as “monkeys” or “monkey people,” by Chinese employers.

However with so much wrapped-up economically in China-Africa bilateral deals, it is not surprising recourse from either Chinese or African government officials has been minimal at best. In fact, just as essential is the economic factors of China-Africa cooperation, “a major component of this relation is scholarships.” According to an October 2018 New York Times article, money lent from China to African countries, has left many African nations in debt and reliant upon China’s commercial resources.

However with so much wrapped-up economically in China-Africa bilateral deals, it is not surprising recourse from either Chinese or African government officials has been minimal at best. In fact, just as essential is the economic factors of China-Africa cooperation, “a major component of this relation is scholarships.” According to an October 2018 New York Times article, money lent from China to African countries, has left many African nations in debt and reliant upon China’s commercial resources.

Despite China’s air of goodwill, these types of multilateral deals with the People’s Republic leave the recipient nation and its people vulnerable to exploitation and discrimination. With billions poured into African nations from Communist China comes political and economic leverage. So while publicly heralding its relationships with African peoples, many Africans, particularly those who study abroad in the Far Eastern nation, China’s generosity comes with a patina marred with prejudicial practice.

For in reality, though China has anti-discrimination laws on their books, there is little tradition or framework for civil rights currently existent for both citizens and foreigners. Therefore, there is no government apparatus or institution to appeal to or to which to lodge complaint.

By Vincent Amoroso