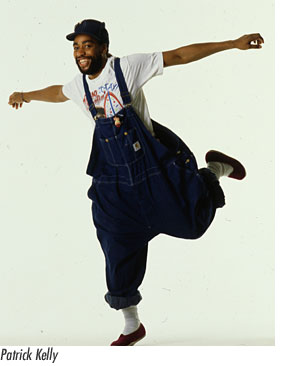

Patrick Kelly was a man ahead of his time. He was the first American and black designer allowed to join the Chambre Syndicale du prêt-à-porter, the French ready-to-wear governing organization. He made clothing that was inclusive of different body types and shapes before it was

The fashion designer also had a great sense of humor and enjoyed making people laugh, he described himself as a black, male Lucille Ball. He once told People Magazine when they asked his age that he was “old enough to be in bed without peeing.” Though he never divulged his age it is believed that the designer was either 35 or 40 years old when he died of complications from AIDS.

Kelly was raised in Vicksburg, Mississippi by his mother and grandmother. He took inspiration for his designs from his experiences as a black man growing up in the south and from his grandmother, who was a maid and would bring home fashion magazines from the white families she would clean for. When he was younger his grandmother once brought home a fashion magazine that did not include any black models and he vowed to remedy this and design clothes for black women.

“My grandmother was the backbone of a lot of my tastes,” Kelly explained to People Magazine, “She was always so pretty to me. I would go to church and look at her across from everybody else and she was a dream.”

Kelly was a self-trained designer, his mother taught him how to draw and he learned to sew from one of his aunts who was a seamstress in Louisianna. After high school, he moved to Atlanta where he would sell the clothes he made and stage fashion shows. He met supermodel Pat Cleveland, who convinced him to move to New York where he attended Parsons School of Design for a year and a half. Kelly did not have the same success he had in Atlanta and found it difficult to launch his career.

“They say the French are snobs,” Kelly told People Magazine in a 1987 interview, “try getting in to see a New York designer.”

After voicing his frustrations to Cleveland, she suggested he try moving to Paris and the next day he received a one-way ticket to Paris. After his move to Paris Kelly made costumes for a French nightclub until 1982 and after that began selling his clothes on the streets in front of a boutique that would later sell his clothes. This was where he found inspiration and created his tube dress with mismatched buttons that caught the attention of Françoise Chassagnac, who began selling them at her boutique.

Embed from Getty ImagesIn 1985, Elle magazine ran a six-page story on Kelly which led to wider notoriety and an increase in orders. By 1987, Kelly was juggling 17 freelance design projects, including a special line for Benetton. In 1988, he received financial backing from the Warnaco group, an American textile/clothing company, and shortly after he was accepted into the Chambre Syndicale. In an interview with Hint Magazine, Dilys Blum, a curator for the 2014 Patrick Kelly exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, explained that Kelly signed the contract right before he found out he had AIDS. Warnaco later pulled out of the agreement not because of his diagnosis but because of noncompliance.

“He was pushing boundaries and they really wanted him to be more mainstream, like Calvin Klein or Michael Kors,” Blum explained to Hint Magazine.

Kelly’s designs featured racist tropes such as watermelons, golliwogs, and pickaninnies. His fashion made a political statement. As Blum explained to Dazed, Kelly “subverted not only fashion but also stereotypes, particularly in regard to race. He played to such assumptions while undermining them.” The smiling Golliwog with gold button earrings became Kelly’s logo and is painted on his grave in Paris.

In an interview with Vice, his former partner Bjorn Amelan talked about the impact of Kelly growing up in the South. Most of his textbooks were hand-me-downs from white school and having to look through the images of blackface

His designs were not just political statements, they were fun, inclusive, and paid homage to Black history, one of his runway designs featured a recreation of Josephine Baker’s banana skirt costume. Other staples of his designs included dice and mismatched buttons. An idea he got from his grandmother who would sew buttons of differing shapes, colors, and sizes to replace the ones missing on his clothes.

Like his designs, Kelly was bold, vibrant, and loved by everyone. By the time of his death in 1990, he had dressed Princess Diana, Grace Jones, Cicely Tyson, and Bette Davis, who was one of his muses. Though his career was short, it is clear that Kelly accomplished the goal he mentioned in a 1986 Washington Post feature.

“I want my clothes to make you smile.”