Author: Kazembe Bediako

WHEN THE EARS OF WISDOM ARE OPENED SO FALLS THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE MASTER

African Proverbs say ‘No man tells all he knows!’

I dedicate my comments to the Shepsu who have helped preserve the glory and majesty of African Culture and African Spirituality so that we their reincarnated forebears could pick up the gems stones of their ancient wisdom. I can remember many years ago travelling on the D train to Harlem on a trip to Liberation bookstore where I bought Chancellor Williams’ The Destruction of Black Civilisation, a book that nurtured my love for African History and the nobility of my ancestors. Equally years later through the majestic wisdom of Dr John Hendrik Clarke I was turned onto a powerful and ground breaking book The Wonderful Ethiopians written and published by Drusilla Dunjee Houston. It was these and so many other books and lectures by African-centred scholars that educated me in regard to the Knowledge of Self and later an appreciation of Self Knowledge.

I mentioned this because as a scholar and child of Africa I have been granted access to a whole new world of possibilities by scholars such as Jake Carruthers, Amos Wilson, Dr. Ben Jochannon and numerous other thinkers. On reflection Chancellor Williams and Drusilla DunJee Houston and previous generations opened the way for the reawakening of the dead, those who Elijah Muhammad defined as being death dumb and blind and lost in the cultural wilderness of the western world. Indeed we owe a great debt of gratitude to our forebears from Khamit through to the streets of Harlem and beyond for opening the doorway for the awakening of the slumbering black masses. According to the author The Children of the Light and the Magic Temple is a novel or so it would appear however, the book clearly draws inspiration from the monumental work of Ra Un Nefer Amen who has tirelessly taught African spirituality for many years[1]. In actuality, without going into a detailed discussion of the mighty body of work penned by Dr Amen one is reminded of the fictional novel Heru the Resurrection which is a pivotal book that highlights the strategic importance of using the novel format to teach the ancient wisdom of Africa to the current generation of Africans.

However, this book review is designed to do four things 1). Explain why this book is important 2). To touch on the core themes expressed within the book 3). To provide an example of the books content via a short exploration of chapter ten. 4). I will conclude the review with some brief remarks. However, for clarity it is important to note that my review is derived from my own level of understanding and thus it reflects my own views which may not accord with the views of others or even the authors.

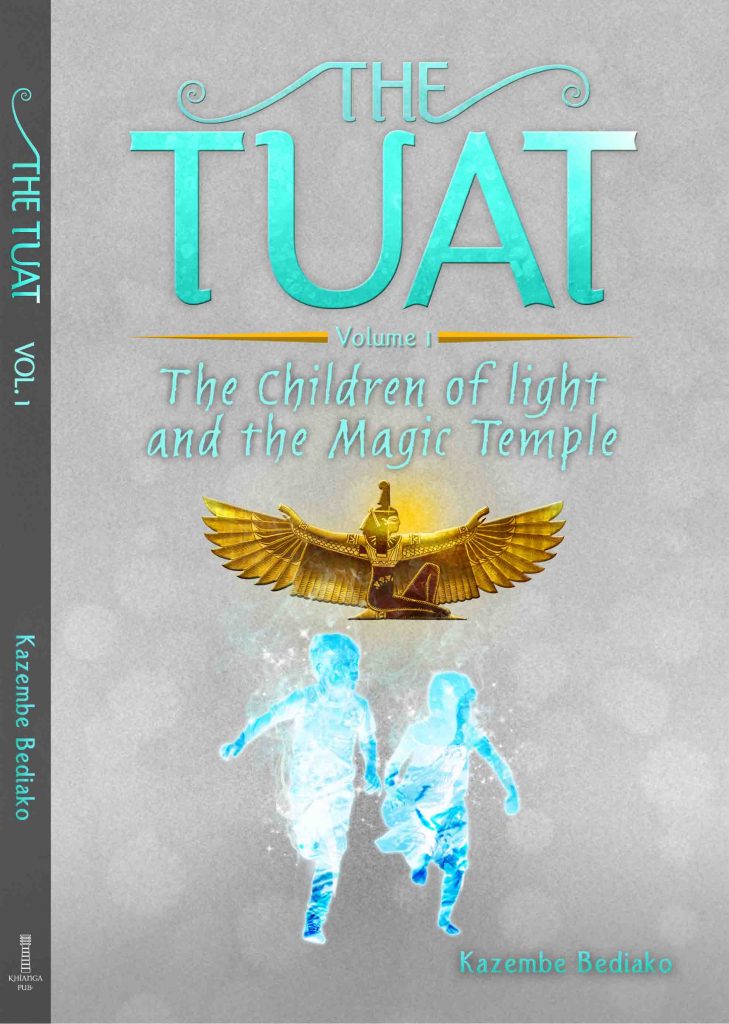

Prior to explaining the importance of this book, it is worth stating what the book is about. According to the author ‘The Story of the Tuat: Children of Light and the Magic Temple’ occurs in a period of Kamitic history leading up to the unification of Taui. Between the creation of the great empire known as Kamit or Taui, the two lands and the time of the fifth dynasty after almost 1000 years the government has become very corrupt under foreign rule’ (Bediako, 2016, IX). The book is dedicated to examining a people’s quest for both personal and collective liberation. However, the premise of this text is to encourage Africans to return to the fundamental principles of African spiritual culture, and to reject the imposition of foreign ideas and the rival philosophy of seitan/sethian power politics which takes the shorter and destructive path towards the acquisition of power. In that sense the battles depicted in this book should be likened to the esoteric interpretation of the principle of Jihad or the battle waged between Set and Heru i.e. a holy war that actual takes place within one’s spirit and within the social dynamics of the larger society.

The importance of this text

It is true that what we glean from any book is dependent on what insights one already possesses; and one’s ability to still one’s thoughts in order to comprehend the deeper meanings and nuances that lay hidden within a book’s pages. This book echoes in and caresses one’s consciousness like a gentle and subtle wind and tacitly suggests that African spirituality is a valuable tool in relation to the reconstruction of African culture. The book breathes life into the hidden history of what Dr Ben called Hapi Valley Civilisation. While Cheikh Anta Diop and Dr Ben have provided historical insights into the Hapi Valley Civilisation, this book reveals startling facets of African spiritual culture. The book engages in an archaeological investigation of the inner planes of African and universal consciousness. While it may be described as a work of fiction; it transcends this limited description as it provides access to an ancient and contemporary mystical world that can be and has been accessed by the author! In truth, to successfully engage with this book we must depart from a Eurocentric praxis pertaining to the linear understanding of history and time. Given that most African people are unaware of their stolen legacy, due to European scholar’s systematic erasure of real African history most (even educated) African’s have lost a true knowledge of themselves and their culture.

Equally, African’s have scornfully abandoned and no longer practice the spiritual systems that paved ancient Africa’s pathway to power. While the author has drawn on the work of Ra Un Nefer Amen the book stands on the broad shoulders of our revered ancestors like Boukman, Blyden and Garvey, who exalted us to walk in the footsteps of our past in order to construct a roadmap for our liberation. Given the authors immersion into African spirituality and African history he is able to tap into the historical and cerebral pathways of our African forebears. Thus, the author is able to unearth the complex metaphorein of a people whose oppressed status precludes them from being credited with the creation of the Hapi Valley Civilisation. In particular, the book correctly indicates, without a hint of prejudice or bigotry that we the diasporian Africans who Elijah Muhammad referred to as the Lost Founds lost in the wilderness of the western world; are the original people of the planet and the architects of a civilisation that lasted over four thousand years. For that alone this book is worth reading! Nonetheless I would still caution you into thinking that what my person experienced will reflect your own experience in relation to the book as the keys to unlock one’s understanding are related to the elevation of one’s consciousness.

The Core Themes

Whether stated implicitly or not the book links the past, present and future in a quest to understand, adhere to and cultivate the 11 Laws of existence that were carefully examined and defined in Ra Un Nefer Amen’s book, Maat the 11 Laws of God. The premise of Bediako’s book is based both on the spiritual and scientific understanding codified in Dr Amen’s UAAB text! It indicates that man has four brains, the R complex/reptilian, mammalian and human brain plus the frontal lobe which is the seat of man’s divinity (Amen, 2013). At heart Bediako’s approach underscores the notion that man, and woman have the ability to transcend the animal and human existence in order to awaken their divinity. While Bediako does not directly mention the two aforementioned book his story shines a light on the scientific content of Dr Amen’s work in a fluid and dynamic way.

The point being the book highlights the sacred science enshrined in African cosmology additionally the book provokes the reader to question the western worldview that underpins the world’s foremost religious systems. Undoubtedly, the book challenged me to stop thinking and trying to absorb the meaning of every word. Rather I elected to still my thoughts and sail downstream and absorb the light and wisdom hidden within the mystic’s words which became etched into my imagination. Eventually I discarded my scholastic training so I could embrace the truth buried within the treasure house of African cosmology that has been reborn within a small cadre of returned ancestors dedicated to the restoration of Hapi Valley culture. A core facet of the authors method is the infusion of an African-centred concept of time that illustrates the book’s characters’ ability to reincarnate back onto the physical plane in order to fulfil their divine destiny. This fluid understanding of time highlights the omnipresence of consciousness and its ability to be transferred across time through genetically fluid ancestral lines that allows the returning ancestors to assume new bodies whilst being able to access the accumulated wisdom of past lives.

The book also examines and challenges our conceptualisation of consciousness pertaining to being awake, sleeping and dreaming. It is not surprising that mystics and adepts of all cultures explore and articulate the inner meanings and functions of being, awake, sleeping or dreaming. In this text, the author causes one to reflect on the shallow meanings ascribed to commonly used definitions of dreams and awakened states. In that sense, the text is inherently philosophical as it launches us into the complex yet seemly simplified consciousness of our noble ancestors the Kamau. The references to the mountains of the moon and the Twa people is indicative of the evolutionary and cultural migration patterns of the Hapi Valley civilisation. The idea being that Egypt or Khamit was born within the inner regions of Africa and that Khamit’s wisdom and power was a result of an accumulative historical process where the various people of the Hapi valley infused their cultural, ethnic and spiritual knowledge into successive migratory patterns which formed the basis for the creation of ancient Khamit which became the capstone of African civilisation.

Chapter 10

Chapter ten makes a number of illuminating points. It opens with the following statement ‘do you understand that you are neither your body or your spirit’ (Bediako, 2016, 95). Here the authors points to the transcendental aspects of the person that we may exist outwardly as an individual but in actuality we are part of the whole that corresponds to Neter or the all in all. This is important as it demonstrates the authors deep and significant grounding in his own ancestral wisdom which in turn corresponds to the universal and scientific laws that transcend one’s ancestral lineage and even one’s cultural orientation. The emphasis here lies in locating the hidden truths and to inform Africans of our legacy, and birth in addition to highlighting the importance of living in accordance with an African way of life through one’s actions as opposed to just disseminating information regarding the substance of African philosophy. The authors use of metaphors as tools of enlightenment is useful and duly noted.

For example, the pursuit of the young girls by Sethian or Setian Watchers throws up some interesting points in relation to standard definitions of both history and spirituality! In this particular scenario three African girls are being pursued by a group man who intend to kill them. The idea that the lives of African’s are in danger from oppressive forces is clearly a familiar one.

Indeed, if you have read the work of our scholars such as Dr Ben, Clarke or Chancellor Williams or examine the lives of Malcolm x, Dessalines, Boukman, Harriet Tubman or Queen Kahina from North Africa, you will recognise that Africans possess a warrior faculty embedded within our DNA. However, unlike the Euro-Asian warrior tradition our military and warrior class is not tasked with leading the nation. The (legitimate) limitations ascribed to the African warrior class is encapsulated by the Yoruba who say, no one loves Ogun (the premier martial Orisha), except in times of war.

The Yoruba maxim has numerous meanings, but it also raises questions regarding whether the African warrior tradition has been abandoned by modern day Africans, and whether we understand that a peaceful warrior can legitimately manifest a martial component when lawfully required. One notes that on page ninety-seven that Ur Aua Abaso whose title Ur Aua indicates he is a King sends five body guards all of whom are Shekems i.e. chiefs and priests to rescue the girls (Bediako, 2016, 97). The implication being that one aspect of leadership resolves around the defence of the peoples interests which raises another set of questions dependant on your definition of defence. Still the recent African history pertaining to the MAAFA and colonialism suggests that this question of defence

in the face of oppression has being a critical factor for Africans both at home and abroad. As African’s existence (since the fall of African civilisation) has revolved around the question of defence whether in Haiti or throughout the Caribbean from Dessalines, Nat Turner, Zumbi and Malcolm, the question of defence and its various dimensions, has engaged African intellectuals, priests and warriors.

The answer to the question lies within the context of a wholistic understanding of African cultures which gave birth to the Maroons, and the great Kingdom of Palmares that flourished during the period of enslavement in Brazil. Needless to say, the perspectives of Marcus Garvey, Amilcar Cabral and Diop, that the heart beat and core foundations of defence (in all its permutations) lies within a people’s culture. A lawful appreciation of the author’s story is indicative of the understanding that culturally and spiritually evolved people can legitimately possess a territorial imperative designed to maintain and protect their interests without being in opposition to their spiritual principles. However, I digress back to the book.

On page ninety-eight we are told that Nehahaher is hunting the girls because ‘one of them is a direct descendant of the Amen Dynasty [and that her] DNA carries the evidence of a Kamau Bloodline as the root of Khamit’ (Bediako, 2016, 98). The author’s comments tacitly convey the importance of ancestral bloodlines, the implication being that culturally enlightened people respect, nurture and protect their bloodlines as said bloodlines carry the seedlings of their own salvation. This is important as the actions of the Setian nation indicate that it is committed to the systematic destruction of the Khamitic in order to secure the continued oppression of the people! Strikingly the noble bloodlines of Africa were scattered during the MAAFA and like the body of Ausar they have been deposited in different geographic locations and are waiting to be retrieved, made whole and resurrected.

However, the most intriguing aspect of the chapter was the statement regarding the EDFU scrolls and the corresponding claim that ‘according to these scrolls, civilisation came from the South by a band of invaders from the Ware Nations under the leadership of the Shemsu Heru Kingship’ (Bediako, 2016, 99). The geographical aspect of the authors statement accords with Dr Ben’s thesis that the ancient Egyptians stated that they came from ‘the foothills of the mountains of the Moon were the God Hapi dwells’ (Ben-Jochannan, 1989), equally the role of the Shemsu Heru is intriguing and enigmatic. Despite having read volumes of books, the statements regarding the Ware Nations was new to me. I slid off in my imagination wondering whether the author had a hidden historical manuscript that would expand and elucidate on some of the gems lodged within this small book. Ultimately, I began to question whether l have dedicated enough time to my own spiritual liberation? How can we empower our brothers and sisters with knowledge if we have not properly fathomed the depths of our own understanding? Since Neter needs us to come into the world then our failure to liberate the Self has consequences beyond our own existence. The point is we are not really doing the work of the Shepsu or those who sacrificed their lives so that we could find the doorway to our spiritual salvation. Rather, for the most part we dissipate our energy and resources working in routine and mundane jobs that do not serve our collective interests!

The Heruic principles and the Ogun and Herukhuti persona types presented within this book are skilfully woven into the rich cultural and spiritual tapestry of this book. Still, as refreshing as it is to consider and reflect on the internal and external battles fought in this book; It is imperative that we comprehend an important message of this book concerning time. That time does but does not exist at the higher levels of existence! And that what we refer to as time is concrete, ethereal and permeable! Thus, we should see that history is cyclical, and that the thematic patterns of history essentially remain the same. So, the ancient battles, the pursuit and the related oppression that manifested on the physical plane both within the book and our history are as relevant to us today as they were yesterday. In addition, the author provides insight into the correct use of the Ying and Yang (polarities) to both cultivate and ring-fence martial power. Towards the end of the chapter on page hundred and two the author mentions a powerful meditation that Ptah-Hotep and Iswande do in order to utilise the power of the spirit to assist in mounting the rescue of the girls taken by the Sethians. The limitations of physical force and or the balance required to meet the challenge is exemplified by one of the Shemsu Heru warriors who says in relation to the priests ‘we don’t have time for meditations’ (Bediako, 2016, 102). This classic tension between the use of physical force and spiritual power reminds one of the Kybalion which states that all contradictions are resolved on higher planes of existence. Thus, the chapter closes by showing that the warrior impulse exemplified in the forward momentum of the Trigram Chen must be augmented by the insight/knowledge and deep reflection encapsulated in the I Ching Trigrams of Li and Ken which indicates that any outward (legitimate) manifestation of physical power must be undergirded or assisted by the internal cultivation of wisdom and the power of the spirit. Thus, the key to is working within the inner planes to cultivate spiritual power so we can safely express and manifest it on the physical plane. Therefore, it is possible to be both a priest and a warrior and to meet and resolve earthly challenges and the wise recognise the need to the cultivate the eleven powers as a way to ensure one’s success.

Concluding remarks

Recently I was asked a seemly simple question in diasporian Ebonics, who you be? It would be easy to say I knew the answer to the question except knowing is not in the past tense as knowing is placed squarely in the now! Hence the inability to recall the right answer at any time provides us with a lesson in humility. To know means in all circumstances and at all times and knowing is exemplified in doing or completing the correct action automatically. To be frank to know requires a peaceful disposition, vitality and an awareness of the scientific laws that underpin reality. Reading this book result in a flood of revelations that have taken time to process. By entwining the thematic strands that characterise the existence of both diasporian and continental Africans whose experiences have kept them trapped within the conceptual confines of Western culture and lost within the opaque cultural desert of an alien culture; the author provides the reader with the rare opportunity to free our African minds. Can you hear the call of Sankofa the mystic and enigmatic bird, can you see the majestic Bennu bird rising from the ashes of the MAAFA! Are you ready to embrace your own spiritual culture! Like the metaphor of Auset, the book served as a reminder that all fragments most be made whole and that despite the odds and seeming opposition we must hold fast to our divine destiny. Thus, do not be oppressed by the burdens of life to the extent that you fail to understand or live your destiny. May the author continue the mission to propagate the teachings of our enlightened ancestors who fought bled and died to maintain our wisdom traditions. Oh, Africans remember your teachings and culture were once the light of the world, so teach our people and together we can teach the world; so, it was before and so it will be Amen!

Dr Kheftusa Akhiba Ankh

Khianga Publishing 2016