By Maitefa Angaza

“Some of the founders were influenced by RAM, (Revolutionary Action Movement), and sought to promote radical leftist views through Black Dialogue. But the others considered themselves Cultural Nationalists, who, though militant in their thinking, did not align themselves thus.”

Edward Spriggs, founding editor Black Dialogue

There has always been a need for independent vehicles of Black thought and creative expression. Print pages that celebrate our literature and art, claim agency over our discourse and prioritize our concerns, are still an imperative. Those engaged in the risky business of publishing while Black, have shiny new tools to work with but some of the same old frustrations. There are still interlopers disputing our right to free speech and seeking to obstruct the dissemination of our ideas.

Although publishers can now engage a targeted audience with amazing speed and ease, moral and material support remains critical for the outlets interested in presenting challenging writing and writers, showcasing provocative visual artists, and/or addressing issues of inequity and injustice. These publications carry forward the invention and resilience central to our survival.

In this issue, we’ll take a look back at Black Dialogue magazine, a celebrated fixture of the U.S. Black Arts Movement, which spanned 1965-1975. The magazine is an inspiring reminder of what can be done when lit meets grit.

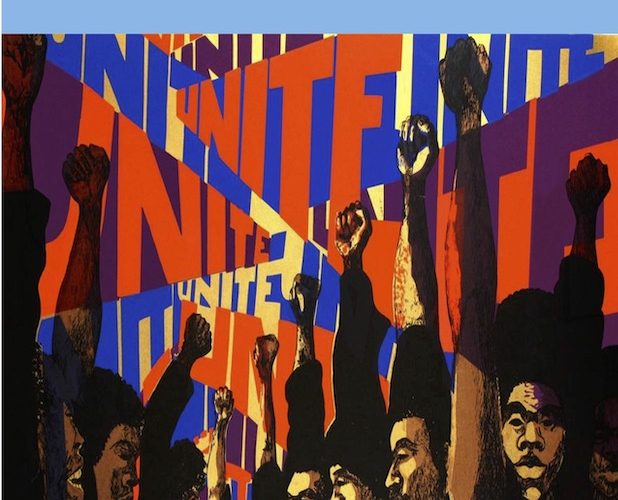

Through the literary activism at its core, the Black Arts Movement (BAM) declared the people’s urgency for agency. Although criticized by some at the time for being merely about culture and optics, the BAM helped to raise awareness and

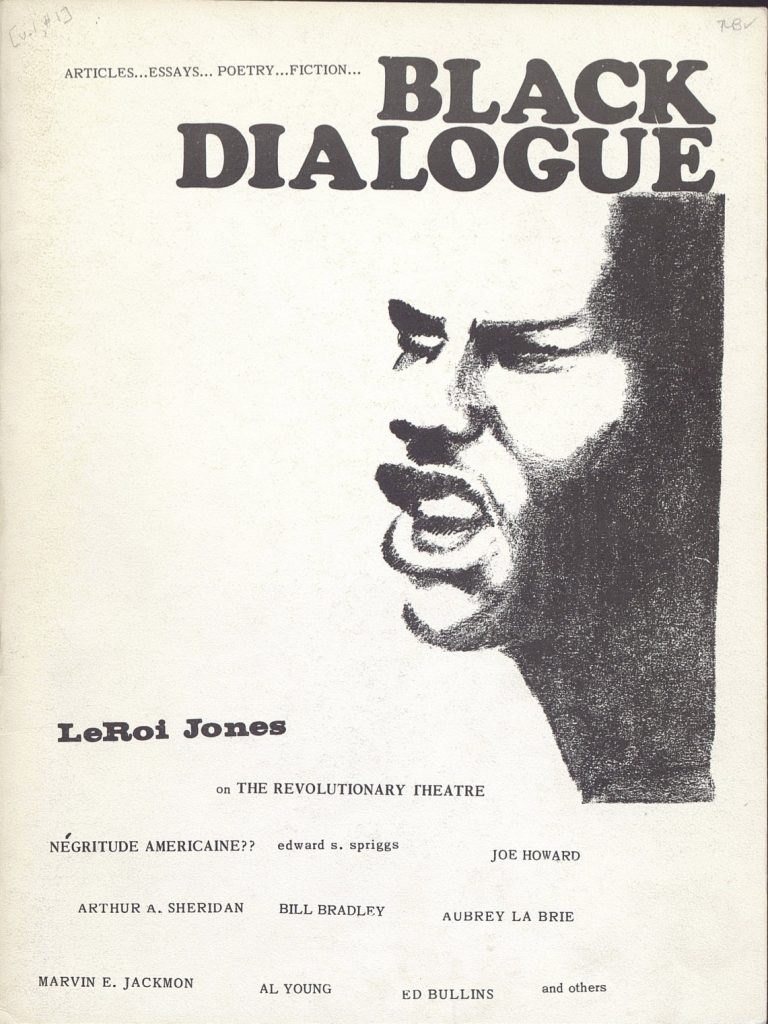

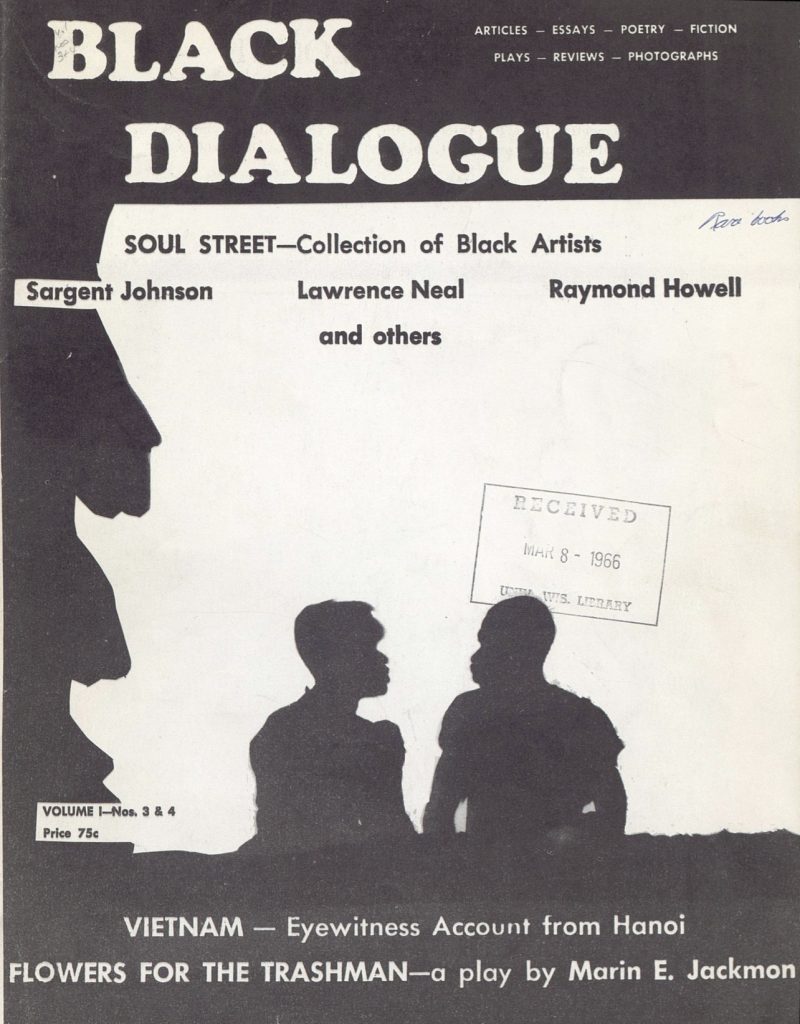

In 1965, a group of Black students at San Francisco State College (now University) created a publication dedicated to the legacy of Malcolm X. It was designed to give voice to fellow students, as well as to artists, writers and other thinkers in the surrounding community. To get the full story we spoke with Ed Spriggs, a founder, and editor of Black Dialogue (BD) and the Journal of Black Poetry. He’d later head the Studio Museum in Harlem, Hammonds House Museum in Atlanta and serve as Northeast U.S. region director of FESTAC ’77 – the Second World Festival of Arts and Culture in Lagos, Nigeria.

“Each one of us was a part of the student movement,” Spriggs said of the magazine’s founders, “at San Francisco State we were the Negro Student

Black Dialogue was an all-hands-on-deck endeavor. The writers were also the office staff, printers, and distributors. The first issue was printed on a mimeograph machine, but the students quickly formed a relationship with Marcus Bookstore owner and Movement printer, Julian Richardson. He saw they were serious and invited them to his print shop, where he’d set up and supervise, while they ran the presses to produce their own publication.

There was a clamor for inclusion from the outset, as writers and artists now had a vehicle for sharing and validating their work, as well as a view of what others were thinking, feeling and creating. But there was a fissure in the structure that would soon lead to a split.

BD’s editorial board consisted of Editor-in-Chief Arthur A. Sheridan, Dingane Joe Goncalves, Edward S. Spriggs, Abdul Kaliem, Joe Howard, Aubrey Labree, and Sidney Schiffer. Some of the founders were influenced by RAM – the Revolutionary Action Movement – and sought to promote radical leftist views through Black Dialogue. But the others considered themselves Cultural Nationalists, who, though militant in their thinking, did not align themselves thus. The two factions parted ways, with the leftist group going on to publish a new publication entitled Soulbook.

Black Dialogue continued to be inundated with poetry submissions, so Goncalves – “doing yeoman’s work,” said Spriggs – created the Journal of Black Poetry as an additional outlet. It went on to become one of the most influential publications of its time.

“He (Goncalves) remained a part of the editorial board of BD. During this time I was moving to New York City, having finished my undergraduate work and intent on getting the hell out of San Francisco and getting somewhere ‘real’ – so I thought. So we got the idea that I would be the East Coast editor of BD and a contributing editor of the Journal of Black Poetry.”

Edward Spriggs

Spriggs says BD was dismissed in some quarters because “it wasn’t reaching for the standard that was the canon of the white world, although something of ours would occasionally be picked by Dudley Randall or Margaret Burroughs or even Hoyt Fuller in his Black World.”

“We didn’t know anything about distribution. Well… we didn’t know anything about publishing magazines either – but we were doing it! It was a seat of your pants, learn as you go, kind of thing,” Spriggs explained, “We weren’t even trying to get into a regular magazine distribution channel. We wanted the people who were like us. We wanted to spread the notion that there were things we could do institutionally in art, there were things we could do to support the political activities going on, and most importantly, to support each other as we attempted to be creative in our lives.”

Additionally, outside of the arts community and the one that was germinating around conferences and political activity, there was no established audience for BD in the wider community (people were reading Ebony and JET.). But the founders were committed; without institutional or corporate money, BD elbowed its way into the narrow space occupied by publications such as Negro Digest and Liberator. One did not need an established name or reputation to have work published in BD, only talent and a heart for the people.

“We had to create a following by gaining exposure off-campus and outside of the artist community, so initially the word spread through the founders attending conferences and organizing discussions. As East Coast editor, I went to Philly, to DC, Detroit, etc., to share the magazine and solicit manuscripts. The audience was built piecemeal through that type of activity, word-of-mouth eventually worked, and soon it was hot! If you got a Black Dialogue, you shared it with about six people, at least, back in that day,” Spriggs said.

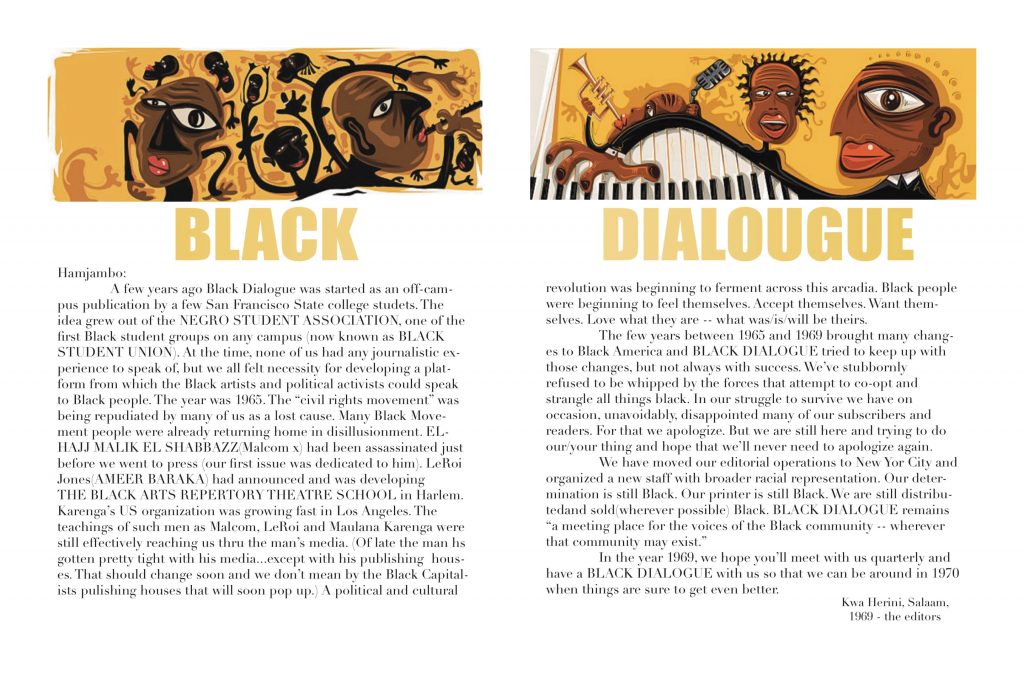

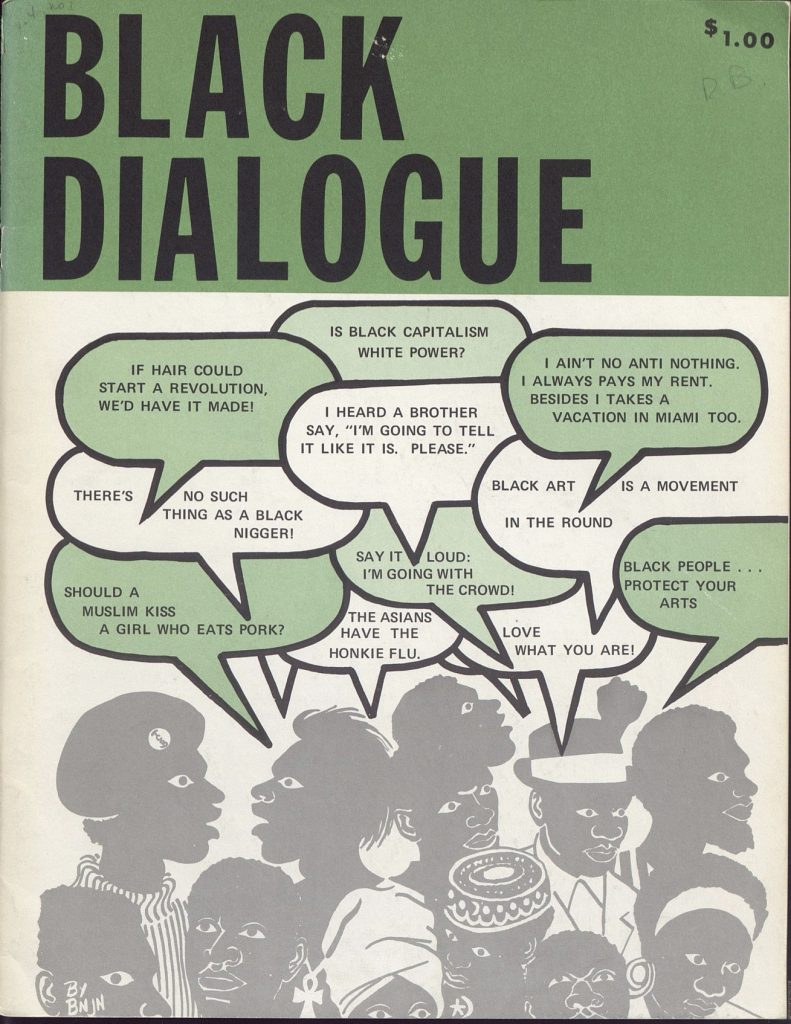

The issue pictured here, SPRING 1969, Vol. IV, No. 1, was published in New York City, the first issue following a year-long hiatus. Annual subscriptions were $2.75. The editorial staff at this time was a talented and intrepid crew from across the country. Some had earned, and others would later come to earn artistic or activist acclaim.

The New York / East Coast team consisted of; Edward Spriggs, Nikki Giovanni, Jaci Early, Elaine Jones (Kimako Baraka), Sam Anderson and James Hinton (photography.) In San Francisco / West Coast – Joe Goncalves; Mid-West – Ahmed Alhamisi and Carolyn Rodgers; Southern USA – Julia Fields, Akinshiju and A.B. Spellman; Africa – Ted Joans in West Africa and Keropaetse W. Kgositsile, editor at large.

On the cover of this issue of BD, artist Ben Caldwell renders a cluster of talking heads representing the diversity of Black people found in urban areas across the country. The text, written by Spriggs, presents the prevailing opinions on offer at campuses, on street corners, at organization meetings or the dinner table – with a couple of provocative additions in the form of philosophical statements.

Inside we find, “Dialogue with Aum,” Ed Spriggs’ interview with the gifted San Francisco sculptor, complete with photos of Aum’s work. Nikki Giovanni’s piece, “And What About Laurie?” reviews the film,Uptight addressing, in particular, the role played by Ruby Dee. There was also, “And They Will Be Astounded,” a short story by Melba Kgositsile and Will Halsey’s one-act play, “Judgement,” about the arrest of Amiri Baraka for carrying a weapon during the Newark riots.

The powerful poetry in the issue included: Amiri (Ameer) Baraka’s, “All in the Street”; Jayne Cortez’s, “How Long Has Trane Been Gone?” and “When Brown Is Black (for Rap Brown)” by Keorapetse Kgositsile. There was also “Passed On Blues,” by Ted Joans; “dance like an adjective to you,” by Will Halsey; “Dreams,” by John Farris and “Afro,” by Ruth Mambo McClain.

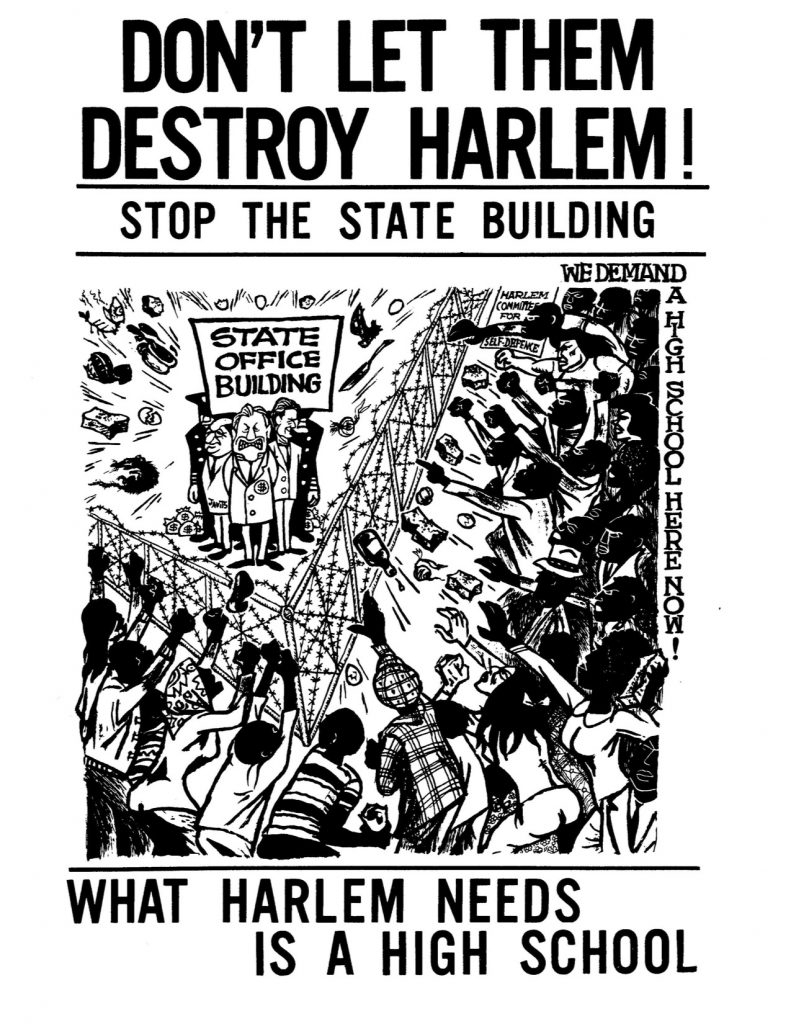

“The Fox Section,” a photo essay, was a regular feature celebrating the beauty of Black women. This issue also includes a poster depicting a protest at the planned construction of the Harlem State Office Building, various illustrations, several ads

Other issues of Black Dialogue contained a wealth of art, insight, provocations, and prose. I

There were also poems by Sonia Sanchez, art by Tom Feelings, a piece on Duke Ellington’s snub by the Pulitzer Prize committee, others on police brutality in San Francisco, U.S. aggression in Santo Domingo, “The Future of Soul,” and much more.

Photographers Doug Harris and Rufus Hinton had been active in SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) before moving to New York. They provided work for various features and arts pages, and, along with Jack Harris, contributed regularly to “The Fox Section.”

While the need remains for daring and thought-provoking publications – be they news, arts, style-focused, related to a societal or political issue, or an intriguing amalgam of all these– the need for independent thought is urgent. We owe a debt of gratitude to those who follow this passion with an ear to the voice of the people.

Some closing words of advice from Edward Spriggs:

“I’d say to those looking to put out a physical magazine now – don’t involve yourself with people who are not on the same page as you, maybe politics is at the root of everything – who knows? ” he said, ” And to catch up with the history of the Black Arts Movement, there’s a book titled, The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s by James Edward Smethurst, it’s a very thorough and embracing piece and it covers activity across the nation.”

Edward Spriggs