Beginning on Africa Day on May 25th to World Oceans Day, June 8, 2020, officials and delegates from all over the African continent, as well as representatives of the Peace and Security Department and Department of Political Affairs of the African Union (AU) met for a series of virtual conferences, presumably, with a noted sense of urgency regarding the collective and ambitious effort to end all conflicts in Africa by year’s end.

“Silencing the Guns in Africa by 2020” or STG, as it has come to be known, has been a momentous project and the brainchild for the likes of the Commissioner of Peace and Security, Ambassador Small Chergal and the Commissioner of Political Affairs of the African Union, Ambassador Cessouma Minata Sernate for some time now. Notably picking up steam in late 2019, the initiative to usher in a long sought-after conflict-free era on the African continent has been the focal point of nearly every multi-national conference in Africa since that time.

A Pan-African Parliament met in Ethiopia in November 2019 o focus on the roles women and children should play in Silencing The Guns movement. The Parliament also recognized the inextricable link between conflict and socio-economic development.

“One cannot exist without the other,” urged Ambassador Ramtane Lamamca (picture to the below), an African Union High Representative to STG, who cited how the combination of crisis and economics was high on the list of root causes of war.

During the past few decades, Africa has been awash in cross-border and civil conflicts that has pushed a number of nations to the brink, cost countless numbers of lives, and displaced millions of persons throughout the region.

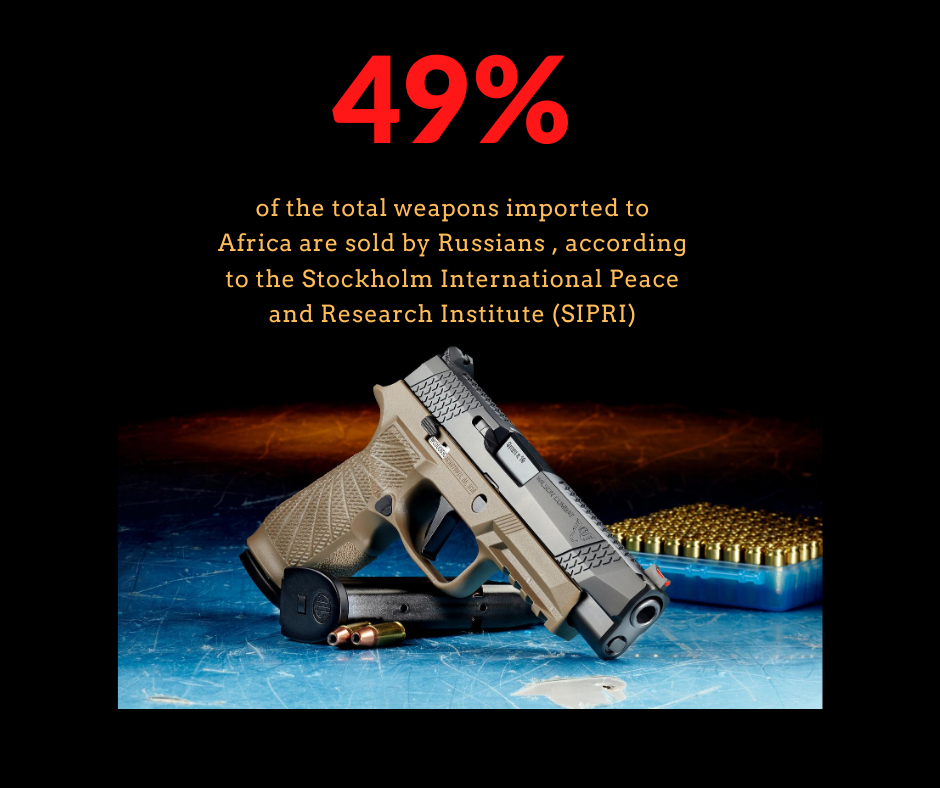

Yet, just as the STG virtual conferences got underway, so too was Russia. For Russian companies, like the state-run, Rosoboronexport, ceaseless war has become big business for which Federation-produced weapons have played a increasingly prominent role in Africa.

49% of the total arms imports to Africa are sold by Russia, according to the Stockholm International Peace and Research Institute (SIPRI) as of 2020. That percentage rose sharply since 2018 when Russia produced 35% of the weapons sold on the continent. This staggering influx has made Russia, by far, the largest pipeline for weapons in Africa to date, which has appeared to run counter to the AU’s initiative.

Indeed, as the African Union made clear the urgency for a campaign to end armed conflicts throughout the continent. Last year, Russian Federation President Vladamir Putin hosted the Russia-Africa Summit in Sochi, which showcased, for scores of African delegates and buyers, military equipment which included combat jets, assault helicopters, bombers, missile systems, as well as small arms.

With arms trading encompassing approximately 39% of the Federation’s defense industry’s revenue, the meeting in Sochi punctuated Russia’s intent to lengthen its already long list of African buyers and “to expand interaction with Africa by developing beneficial trade and economic relations and supporting regional conflict and crisis prevention.”

This push for a longer reach into Africa for the sale of weapons appears in stark contrast to the assessment of the Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, approved by President Putin in November 2016, which notes, “efforts to expand and upgrade military capabilities and to create and deploy new types of weapons undermine strategic stability and pose a threat to global security.” One example of such blatant contradictions can be seen in the case of Algeria, whose government represents the most avid buyers of Russian-made military hardware and has used such arms to forcibly remove Sub Saharan peoples and abandon them in the desert.

Recently Algeria’s purchases have included bombers, attack helicopters, and submarines. Such an uptick in arms sales to Algeria from the Russian shows the Federation is, according to Bradley Bowman, a Senior Director of the Center on Military and Political Power at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, “making an effort to try to increase influence in North Africa.” In recent years, Russia has added Libya and Egypt to its growing stratosphere of clientele in North Africa.

Such large-scale purchases of weapons by African countries from Russia is hardly happenstance, which makes the AU’s push to “Silence the Guns in Africa by 2020.” a laborious and problem-fraught task. Adding to the difficulty of resolving a number of long-standing conflicts on the continent, is the increasingly obvious lack of cohesion between the Federations commercial endeavors, socio-political agenda, and its own stated doctrines.

For instance, Section III, part 21c of the Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation reads, “the main task of the Russian Federation to contain and prevent military conflicts: to maintain global and regional stability” Yet according to a Senior Fellow in Carnegie’s Russia and Eurasia Program Paul Stronski, “they [Russian arms] have helped fuel violent conflict and gender-based violence in various parts of Africa.”

Much to this same regard, to keep the sale of arms flowing, Russia has also engaged in debt release for several Africa nations, like Algeria, who might not otherwise be in a position to increase the size and scope of their weapons purchases. Additionally, many of these weapons often end up, either by theft or corruption, in the hands of unintended recipients, which fuels other local and regional conflicts.

One way Russia can perpetuate such a disconnect between its government’s stated policies and the activities of intermediaries like Rosoboronexport is because within the Federation there are no civic organizations that track international weapons sales. In fact, Russian defense companies are not required to publicize or otherwise report either the type of number of weapons they sell and to whom they are sold to. So, by and large, the defense industry in the Russian Federation operates in the shadows, shrouded in secrecy from all except a select few.

There are cacophony reasons that make Russian-dealt weapons more attractive to African buyers. As there are a number of totalitarian regimes in Africa, such as Guinea, Zimbabwe, and South Sudan, for example, Federation weapons are sought after because, “arms deals with Russia do not demand political and human rights conditions.” Furthermore, Russian weapons are both cheap and reliable, which makes them a more equitable commodity than weapons produced by the United States and other Western nations.

Although the African Union and its member states have made part of their effort to “Silence the Guns,” an examination of the root causes of conflict, the Peace and Security Council has also highlighted the danger posed by heavy inflows of weapons, most notably small arms, into Africa has compounded the difficulties intrinsic to the initiative. Certainly, the unhindered influx of weapons from Russia to its now-list of 21 century partnerships in Africa, will add more challenges to an already daunting task of “Silencing The Guns.”

By Vincent Amoroso