George Stinney and Willie Francis: Two young Black individuals who were executed in the 1940s for crimes they did not commit. They faced unfair trials, coerced confessions, and racial discrimination by the justice system.

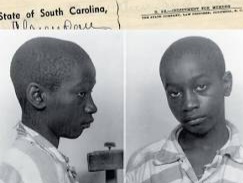

George Stinney Jr. was born in 1929 in South Carolina, the youngest of five siblings. At 14, he was falsely accused of murdering two white girls, Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 7, in his hometown of Alcolu.

Within an hour of being taken into custody, without his parents present, Stinney confessed to the crimes, though the confession was likely coerced. He was quickly indicted by an all-white jury, and despite scant evidence, questionable confession, and lack of due process, Stinney was convicted and sentenced to death by electrocution. On June 16, 1944, just 83 days after his arrest, George Stinney Jr. died in the electric chair. At 14, he was the youngest person executed in the 20th century.

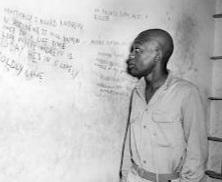

Two years later in Louisiana, a 16-year-old black field hand named Willie Francis was accused of murdering his white employer, local pharmacy owner Andrew Thomas.

Police obtained questionable signed statements from Francis, and he was swiftly sentenced to death by an all-white jury after a one-day trial.

On May 3, 1946, Francis survived a botched electrocution when the chair malfunctioned. After appeals reached the U.S. Supreme Court, the ruling allowed a second execution attempt. On May 9, 1947, Willie Francis, just 18, was successfully executed.

The parallels in these young lives highlight deep flaws within our legal system, especially when it comes to protecting juveniles and black Americans. Stinney and Francis faced death sentences, enforced by all-white juries, within days of being arrested. They likely faced coercion, without parents or lawyers present. Gross miscarriages of justice can occur when proper protections are not in place.

Juvenile death penalty: The practice of executing people who committed crimes when they were under 18 years old. The U.S. Supreme Court banned this practice in 2005, but before that, 226 juvenile death sentences were imposed and 22 were carried out.

As we examine these cases from our modern view, several vital reforms are illuminated that could prevent future injustices:

- Enshrining consistent, stringent protections for minors across all states – no execution, sentencing limits, requirements for counsel, thorough investigation of coercion.

- Mandatory racial bias, sensitivity, and human rights training for all in the legal system – police, lawyers, judges, juries. Oversight committees and accountability measures for discrimination.

- Abolition of the death penalty system, which is irreversible, inhumane, applied arbitrarily, and prone to racial bias. Advocacy and alternatives can end state-sanctioned execution.

- Higher standards of evidence. Coerced confessions are common and unreliable, too often leading to wrongful convictions. DNA testing, thorough forensics, and questioning standards must improve.

- Reexamination of past convictions where bias or lack of due process likely occurred. Posthumous legal proceedings like those undertaken for Stinney’s exoneration in 2014.

Justice reform: The need for legal and social changes to prevent future injustices, especially for juveniles and Black Americans. Some possible reforms include protecting minors’ rights, ensuring due process, eliminating racial bias, and abolishing the death penalty.

While past injustices cannot be undone, by honoring lives like George Stinney and Willie Francis, we can demand a more just legal system for all moving forward. With education, activism, and sustained reform, we inch closer to that vital goal each day. Justice, however delayed, must not be denied.